Researchers and clinicians alike get increasingly excited as science advances and the dream of personalized — and more effective — medicine draws closer to reality. But personalized medicine has ethical considerations and unintended consequences to address.

On Tuesday, two experts explored these issues during the session and panel discussion Ethics of Precision Medicine & DTC Genetic Testing.

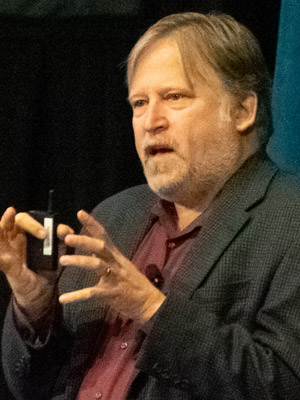

Paul Root Wolpe, PhD, Raymond Schinazi Distinguished Professor of Jewish Bioethics at Emory University, Atlanta, explored some of the ethical challenges related to precision medicine, which he defined as the ability to classify individuals into subpopulations that differ in their susceptibility to a particular disease or in their response to treatment. Dr. Wolpe, also Director of the Emory University Center for Ethics, used real-world examples to illustrate some of the unintended consequences of precision medicine, including concerns about privacy, the ability to accurately interpret the data, and the potential for emotional stress when something unexpected is discovered, as in cases of false paternity.

“On the whole, direct-to-consumer genetic testing is not really a valuable resource yet, and, on occasion, has potential to be harmful,” he said.

Dr. Wolpe proposed several measures to alleviate some of the ethical dilemmas associated with genetic testing and precision medicine, including a call for more government oversight to not only protect the data of those who voluntarily undergo genetic testing but to also protect the collateral information that is gathered on relatives of those patients as a result.

He also said strict advertising standards should be enforced to ensure direct-to-consumer companies are accurately representing what their tests can and cannot do. He said there also needs to be increased discussion about genetics and risk by the medical community, and clinicians need to be prepared to counsel patients who undergo genetic testing.

“I believe medicine is turning into a risk-management system,” Dr. Wolpe said. “It’s not just genetic testing, but that coupled with the availability of behavioral and metabolic indicators mean that we’re increasingly able to predict future susceptibility to disease and therefore to discuss patients’ health more and more in terms of risk and specific risk.

“We will soon be able to create risk-management profiles of people for many different kinds of diseases. However, most disease is developmental. You don’t get diabetes in one day. As we push back the precursors of disease, we’re going to get better and better at identifying people in the pre-clinical or sub-clinical state. Still, we will have few cures, treatments or even meaningful management strategies for a lot of these diseases. Instead, we will mostly be informing people of their risk profiles.”

He said medicine is shifting the decision-making to the patient in a profound way — not just regarding treatment, but about lifestyle and management. And unfortunately, having information about risk may not be helpful.

“People are extremely poor at understanding and assessing relative risk,” Dr. Wolpe said. “We can only offer poor information on assessing risk and on mitigating the factors of risk behaviors. No one knows how to translate medical risk statistics into reasonable patient risk management strategies or behaviors. In fact, I would argue our brains are ill-suited to understand relative risk at all.”

Before Dr. Wolpe’s presentation, Timothy Niewold, MD, Judith and Stewart Colton Professor of Medicine and Pathology at New York University School of Medicine, tried to help clinicians understand how to interpret genetic testing results and counsel patients who ask about their genetic risks.

Dr. Niewold, also Director of the Colton Center for Autoimmunity at NYU Langone Health, said the problem is that, for the most part, genetic testing really can’t predict disease risk.

“Even if we could genotype people with direct-to-consumer testing, we still really can’t predict the risk of a lot of our common rheumatic diseases,” Dr. Niewold said. “We’re just not there yet. Obviously, you can predict some of the monogenic diseases, but for most of our common rheumatic diseases, we’re just not there.”

After reviewing the science behind consumer genetic tests, Dr. Niewold showed attendees examples of reports patients may receive and discussed the different types of information they may include, including information on ancestry, disease carrier status, and genetic traits. He said most companies have made their reports clear and easily accessible for non-scientists.

“They try to break it down and say, for example, ‘You do not have the variant tested. It does not rule out your risk of Alzheimer’s, but the thing we looked at wasn’t there,’” he said. “At some point, it always says if you have questions to contact your doctor or genetic counselor, which sort of gets them off the hook for some things. For the most part, they’re fairly interpretable and user friendly.”

That said, Dr. Niewold noted, if clinicians are not comfortable counseling a patient regarding their results, they should refer them to a genetic counselor.