Rheumatology specialists are often tasked with finding solutions to treat a patient’s physical pain. However, research shows that living with a rheumatic disease can also have profound effects on an individual’s mental health.

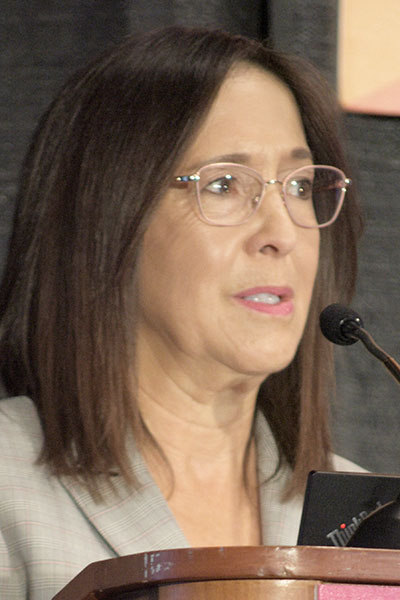

Afton Hassett, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Michigan, delved into the relationship between the psychological impact of rheumatic diseases and their effects on individuals’ physical symptoms and overall well-being during the 2024 Daltroy Lecture Navigating the Unseen — Fostering Mental Health in Rheumatic Disease on Monday, Nov. 18, at ACR Convergence. The session will be available on-demand to all registered ACR Convergence 2024 participants after the meeting through Oct. 10, 2025, by logging into the meeting website.

According to Dr. Hassett, approximately 20% of the U.S. population deals with chronic pain — pain that persists for three months or longer — at a given moment. One of the less discussed but critically important considerations associated with chronic pain is the common development of debilitative cognitive conditions, including depression, anxiety, and loneliness.

“All of these processes result in kind of a decreased sense of self,” Dr. Hassett explained.

To regain one’s sense of self through feelings of joy, connection, calm, and optimism, Dr. Hassett recommended focusing on building resilience. She described resilience as a malleable trait that exists on a spectrum and can be strengthened through teachable techniques.

“When we think about multi-dimensional pain resilience, there are four clear elements: psychological resilience, social resilience, biological factors, as well as healthy lifestyle,” she said. “All of these things can feed into this resilience to medical illness, and when people are more resilient this way, they tend to have a healthier pain adaptation.”

Dr. Hassett shared multiple studies that indicated a clear correlation between positive patient affectations, such as optimism, leading to reports of decreased pain and better health outcomes than from those who did not exhibit these characteristics. Conversely, patients who struggled with negative affectations of loneliness or depression also showed increased disease activity and poorer health outcomes. Dr. Hassett expounded that optimism appears to decrease pain severity by altering endogenous pain modulatory capacity.

She outlined three domains to target to build resilience: increasing healthy positive emotions, changing cognitive processes to be more adaptive, and building social support systems.

The positive activity intervention (PAI) strategies she described are rooted in cognitive behavioral therapy. For example, positive activity scheduling typically involves a patient setting aside time to do something they enjoy three to five days each week and treating it with the same commitment and respect as they would for showing up for an activity like a doctor’s appointment.

Nearly all PAI interventions Dr. Hassett described (additional examples include gratitude diaries, performing acts of kindness, and practices to mindfully savor joy) were simple, scalable, and didn’t require significant costs to patients. They also offer psychological solutions for those who might have negative cognitive associations with other mental health interventions like therapy.

“PAIs are powerful because they’re non-stigmatizing. That’s one of the best parts,” Dr. Hassett said.

She shared that one of her primary goals for the future is for the healthcare community to adopt interventions that build on the unique strengths of the targeted individuals as well as novel treatments that boost patient engagement and persistence.

“We also want to enhance the sense of meaning and purpose because often, people’s view of themselves and their self-image has shifted radically,” she said. “There are many unforeseen consequences of living in these conditions.”

Dr. Hassett also clarified these practices should be adopted by healthcare professionals as well as patients.

“As clinicians who are prone to overworking and burnout, we use these principles ourselves to recharge, to persevere, to find joy, to find happiness, to do the things that we love to do,” she said.

Register Today for ACR Convergence 2025

If you haven’t registered for ACR Convergence 2025, register today to participate in this year’s premier rheumatology experience, October 24–29 in Chicago. All registered participants receive on-demand access to scientific sessions after the meeting through October 31, 2026.