Burnout and rheumatology workplace shortages are reaching crisis levels. Once known as the happiest of all specialties, recent clinician surveys suggest that one-half to two-thirds of rheumatology providers exhibit one or more symptoms of burnout. And workforce shortages continue to worsen.

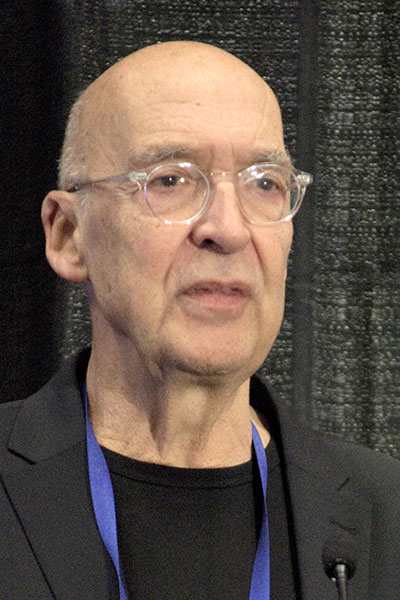

“Our workforce health relies on recruiting, training, and sustaining,” said Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, Professor of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner School of Medicine and RJ Fasenmeyer Chair of Clinical Immunology at Cleveland Clinic. “Burnout is a poison for every piece of this equation.”

Dr. Calabrese opened a special session on Tackling Workforce Shortages in Rheumatology on Saturday, Nov. 16. The session will be available on demand to all registered ACR Convergence 2024 attendees through Oct. 10, 2025, by logging into the meeting website.

Burnout is an occupational syndrome that includes multiple components, Dr. Calabrese continued: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, cynicism, and low sense of accomplishment. Burnout feels very personal, but the major contributors are systemic shortcomings and failures.

“We are in the upper third of burnouts by specialty,” Dr. Calabrese said. “We have a problem to solve.”

The ACR first documented workforce problems in 2015, finding both a shortfall in the number of rheumatologists in the U.S. and geographic misdistributions of rheumatologists. The gap between supply and demand is still growing.

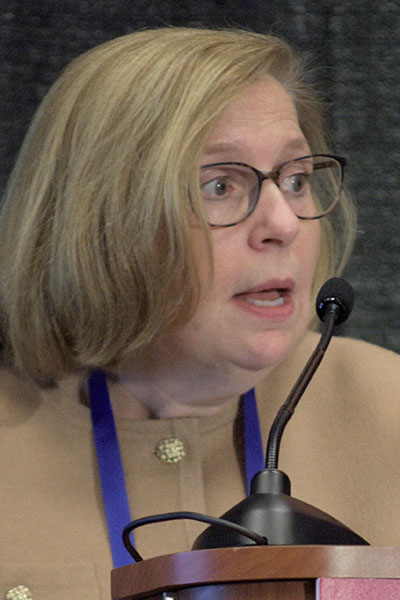

“Every year, we leave 80 to 100 residents [seeking fellowships] on the field,” said Beth Jonas, MD, Professor and Chair of Rheumatology and Immunology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine. “We need more training programs.”

But training more rheumatologists is not enough to close the supply gap, she continued. The profession needs more resources to support the rheumatology career cycle, more advanced practice providers, more best practices to navigate the payer landscape, and more innovative programs to help train primary care and other providers in rheumatology.

Pediatric rheumatologists in particular need more money. The current take-home pay for pediatric rheumatologists averages $181,000 compared to $281,000 for adult rheumatologists and $250,000 for general pediatricians. Not surprisingly, the fill rate for pediatric fellowships has hovered at 75% or lower for the past five years.

“If you’re a resident and love rheumatology, you might see salary numbers and choose adult rheumatology,” said Colleen Correll, MD, MPH, Pediatric Rheumatologist and Associate Professor of Pediatric Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology at the University of Minnesota Medical School. “We have a major recruitment problem in pediatric rheumatology.”

The key driver of lower pediatric rheumatology salaries is the patient population. Adult rheumatologists treat a significant number of Medicare patients, while pediatric rheumatologists treat a significant number of Medicaid patients. And Medicaid reimbursement is about 30% lower than Medicare reimbursement for the same codes.

The ACR, the American Medical Association (AMA), and other groups are pushing to improve Medicaid reimbursement, Dr. Correll said. But Medicaid reimbursement is set at the state level, which means fighting the same battle with 50 sets of state regulators.

Another potential solution is to reduce the three-year pediatric rheumatology fellowship to the same two years adult rheumatology fellows spend in training. The shorter training period could help encourage more residents to select pediatric over adult rheumatology, she explained.

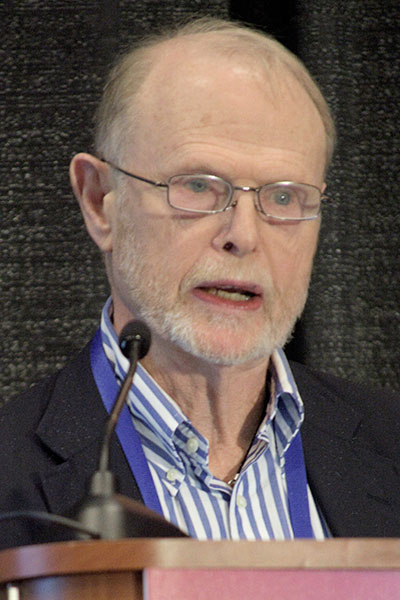

Easing the burnout burden could also improve rheumatology workforce gaps. Burnout is characterized by anxiety and dread of the workplace, said Daniel Albert, MD, Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

Women tend to be more susceptible to burnout due to conflicting burdens at home and at work. Other risk factors include having younger children, high demands on clinical productivity, low job satisfaction, high debt, social isolation, poor work recognition, and moral injury.

Conventional answers to burnout — developing programs to inspire and grow resilience — are both common at academic and healthcare institutes and useless, he said.

“Telling people to grow their resilience is akin to blaming the victim,” Dr. Albert clarified. “You already have resilience.”

Just as the key drivers to burnout are systemic, so are the remedies. Every return rheumatology patient needs a 30-minute appointment, while every new patient needs 60 minutes, Dr. Albert said. If your institution doesn’t allow that much time, he encourages clinicians to push for it, with the clear possibility of changing employers.

Family comes before job, he added, and clinicians shouldn’t be held to “market value” in salary negotiations. There are multiple online sources for compensation comparisons. Current locum compensation is another useful guide for salary negotiations.

“The world of medicine is changing,” Dr. Albert said. “It is becoming more corporate and less academic, big money-like venture. Venture capital, Amazon, and investment firms will dictate how you practice. As a consequence, providers will begin to unionize. The impact of it is yet to be felt, but it will increase midlevels.”

Registered ACR Convergence 2024 Participants:

Watch the Replay

Select ACR Convergence 2024 scientific sessions are available to registered participants for on-demand viewing through October 10, 2025. Log in to the meeting website to continue your ACR Convergence experience.