Health disparities create a gap in the treatment of rheumatologic diseases, and a session looking closer at these disparities addressed specific barriers, the impact they have on patients and providers, and strategic solutions that could help close the gap and improve outcomes for everyone.

Reducing Health Disparities in Rheumatology is available on demand for registered ACR Convergence 2023 participants through Oct. 31, 2024, on the meeting website.

Candace H. Feldman, MD, MPH, ScD, Rheumatologist and Social Epidemiology Researcher, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, outlined the barriers to health equity and a framework for the drivers of health inequities. She used that framework to discuss potential strategies for removing those barriers.

The framework for barriers includes societal structures, exposure, access to care, quality of that care, and health behaviors and biological factors. Among these, a barrier of growing importance is environmental exposure and climate change.

“We know that socially vulnerable and historically marginalized populations are more susceptible to the impacts of climate change,” Dr. Feldman said. “And we know that this is only going to continue to widen the inequities that we already know exist.”

She highlighted another key barrier: lack of access to research and a greater need to recognize the influence of historical mistreatment in research studies.

She advocated for more research into understanding the lasting influence of historic and current policies that perpetuate structural racism.

“Only by truly dismantling those structures are we going to be able to eradicate the disparities that we see when we think about exposures,” she said. “I want to highlight the need for infrastructure, for systematic rheumatology screening but also for interventions.”

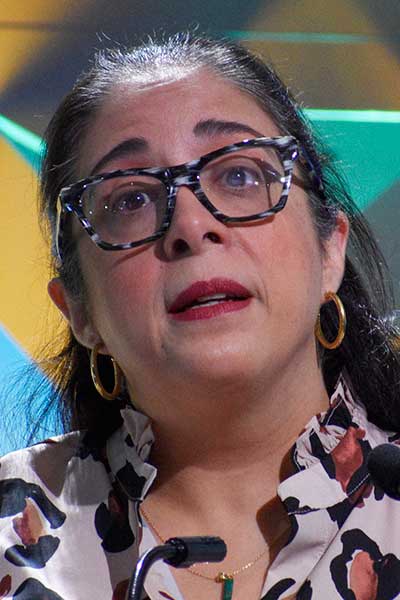

Irene Blanco, MD, MS, Professor in the Department of Medicine at Northwestern University, dove deeper into the impact of health inequity and how it reverberates across the practice of rheumatology.

Health equity issues are affecting the sphere of rheumatology globally, she said. Overall, rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases encompass more than 100 degenerative, autoimmune, and autoinflammatory diseases.

“There is an imperative to do something for our patients,” Dr. Blanco said. “We’ve been trying to beat this drum for many, many years, and yet still, our patients are facing incredibly challenging outcomes in terms of their rheumatic diseases.”

She emphasized that health inequities are preventable, and that the healthcare workforce has a responsibility to work toward dismantling them.

Childhood-onset lupus is one area where major disparities exist. Black children with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have the highest risk of developing lupus nephritis among all SLE patients. Black children with lupus nephritis (LN) are half as likely to get a transplant as white children, and Black children with LN are twice as likely to die compared to white children with LN.

“I’m not asking you to cure racism or poverty,” Dr. Blanco said. “I’m asking you, in your individual clinical encounters with your patients, to think about the small ways you can help gain access for that one patient.”

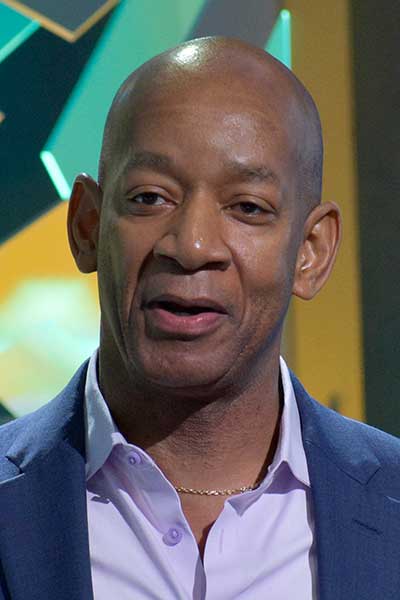

Alvin F. Wells, MD, PhD, FACR, FACP, Adjunct Assistant Professor at Duke University Medical Center, talked about some solutions to health inequities. He is also Midwest Region Director of the Department of Rheumatology for Advocate Health Medical Group and Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine and Rheumatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

He provided an example of a list of fixed versus modifiable factors that drive disparities. Some question fixed factors and ask why they aren’t in the modifiable column, Dr. Wells said. He used geography as an example. It is listed as a fixed factor because moving is not attainable for many people.

Bridging the gap between health disparities and health equity requires action, and he implored attendees to recognize how they can be part of the actions needed to create solutions.

Erasing pharmacy deserts is one way to improve inequity, he said.

“We need creative processes to make sure patients, when they are discharged from the hospital or from your clinic, are getting the drug that you’re prescribing,” Dr. Wells said. “It’s not that they’re not complying. They have no pharmacies.”

He provided several examples of corporate actions to improve outcomes for patients who experience health inequities, such as a pharmaceutical company pledging to partner with more than two dozen historically Black colleges, universities, and medical schools to co-create effective, measurable solutions for health equity.

Insurance is key, he said. Once patients go from uninsured to insured, the gap narrows. He also suggested providing monthly medical funds to people with two chronic diseases. He provided examples of alternative clinic options, such as paying fellows to work at a 24/7 clinic to serve people who work second and third shifts, and dedicating space for telemedicine visits at a library with internet access.

“Don’t say no,” Dr. Wells concluded. “Say, ‘How?’”

Registered ACR Convergence 2024 Participants:

Watch the Replay

Select ACR Convergence 2024 scientific sessions are available to registered participants for on-demand viewing through October 10, 2025. Log in to the meeting website to continue your ACR Convergence experience.