While methotrexate has long been the most common and most effective first-line therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), new and ongoing research continues to shed new light on optimal timing and dosing.

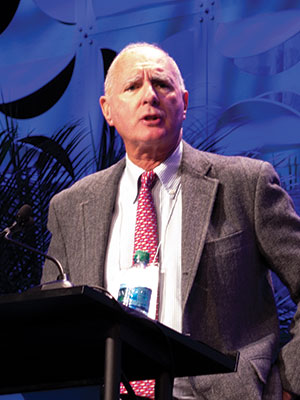

Michael Weinblatt, MD, discussed the latest information on methotrexate therapy for RA, as well as combination use with newer biologic therapies, during Saturday’s ACR Review Course. Dr. Weinblatt is the John and Eileen K. Riedman Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Distinguished Chair in Rheumatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Over the past 30 years, we have experienced an incredible sea change in the treatment paradigm of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Weinblatt said. “When we see a patient with RA today, there is an outstanding chance that, with drug therapy and other modalities, we will be able to allow the patient to pursue a completely normal life and pursue all the activities that they wanted to do before they got RA. And patients with severe RA are fortunately becoming fewer because of earlier intervention and because of the therapies we have now available.”

Developed in the 1980s, methotrexate has become the standard of care worldwide as a first-line, disease-modifying therapy in the treatment of RA, a development that Dr. Weinblatt said has changed the course of the disease for countless patients. But he noted that some questions related to delivery and dosing continue to be studied.

“In the initial FDA application of methotrexate as a therapy for RA, the dosing regimen was based upon the experience with psoriasis, in which patients were dosed 8:00 am, 8:00 pm and 8:00 am one day a week, a so-called pulse-cycle methotrexate, based upon the dermatology belief that the skin turned over every eight hours, which we now know was incorrect,” Dr. Weinblatt said.

Following the initial approval of methotrexate as an oral therapy, Dr. Weinblatt said, rheumatologists around the world, particularly in Europe, began using methotrexate as a subcutaneous therapy.

“It’s important to remember that the maximum doses of methotrexate that were studied in the earlier FDA approval trials were 15 mg per week,” Dr. Weinblatt said. “We now appreciate that, as we escalate the dose of methotrexate to 19-25 mg per week, the bioavailability of oral methotrexate becomes significantly less, while subcutaneous methotrexate offers the advantage of providing 100 percent of the drug to the patient.”

Until recently, subcutaneous methotrexate was not an approved indication for methotrexate therapy in RA; however, the development of new injector systems followed by pharmacokinetic studies led to FDA approval of subcutaneous methotrexate as an option in the treatment of RA.

“Generally speaking, if you’re going to do doses greater than 20 mg per week and you want to ensure absorption for the patient, the subcutaneous option is very attractive,” Dr. Weinblatt said. “If you’re not getting the results you’d like, before you assume that patients are methotrexate nonresponders and decide to add a biologic or a JAK inhibitor, which can carry significant costs, you really should consider first-dose escalating methotrexate to 20 to 25 mg per week either given subcutaneously or split-dose oral, giving them at least four to six weeks to respond.”